- Home

- Academics

- Faculty Bios

- Division of Social Studies

- A Fond Farewell

A Fond Farewell

After 32 years of teaching at Simon’s Rock, Nancy Yanoshak, professor of history and women’s studies, retired in 2016. A dearly loved Simon’s Rock faculty member, Nance passed away on February 26, 2016. Following is an interview by Nance’s colleague and friend, Joan DelPlato, who interviewed her for the Spring 2016 issue of Simon’s Rock Magazine…

JOAN: What brought you to Simon’s Rock 32 years ago?

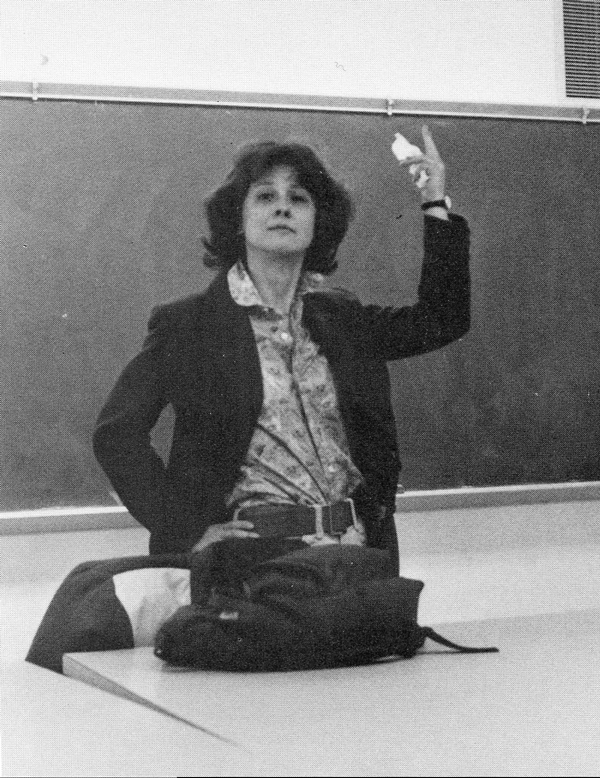

Nance from yearbook 1983

NANCE: I had no idea what an Early College was, but Simon’s Rock was advertising for a European historian, so I decided to apply. I had taken a lot of European history, had a minor in French history, and thought I could teach outside of my Russian history specialty. During the campus interview process I devoted my sample class to Soviet foreign policy in order to show that I could go beyond my area of 16th-century Muscovy. Having some difficulty finding levity in the topic, which I knew would be helpful, I stopped at one point and said in my best hokey Russian accent: “Okeey. Time for djoke.” I didn’t actually have a joke, but folks laughed when I explained that this is what my old Russian language teacher would do when she realized she was losing us. When the application was successful, my friends said “good first job!” I thought so, too, in particular since historians were a dime a dozen at the time (probably still now). I fell in love with the place, and never seriously thought of going anywhere else. I was so impressed by the students, and my colleagues, happy to learn I had a lot of flexibility in what I taught, and was intrigued by our interdisciplinary mission.

JOAN: What have been the most rewarding and the most challenging aspects of your career?

Nance and Joan DelPlato, Hawaii Conference 2008

NANCE: The most rewarding aspects of my career at Simon’s Rock have been the warm relationships that I have been able to establish with friends and colleagues on the faculty, staff, and administration, and the intellectual and personal growth that these made possible. Likewise, my students have been a joy, and their ideas, their accomplishments, and their views on the life of the mind a continual revelation.

It has been wonderful to team-teach with colleagues, and to create courses that responded to students’ needs and new interests. Who knew that a specialist in 16th-century Muscovy would end up teaching courses about Michel Foucault, Apocalypses (secular and religious), gays in American movies, and Love and Death in Western Civilization?

Also rewarding has been my service to the college, in particular as Social Studies Division Head for nearly a decade, and as a codirector for the Institute for Early College Pedagogy. I want to highlight the latter since it built on the Writing and Thinking Techniques that are at the heart of our pedagogy, and was meant to spread the word about our contributions to innovative teaching, in early colleges and just plain colleges. I was very happy to learn that Ian Bickford, our new Provost, is planning a more developed iteration of this project via the Center for Early College Pedagogy.

JOAN: What have been your teaching goals for undergraduate students learning history and historical methodology?

Nance Yanoshak with Lakita Edwards, Commencement 2001

NANCE: I think we all benefit from some degree of “historical literacy,” i.e. a basic idea of important events, processes, people, from the past. As individuals, we would lose our identities and be very vulnerable if we suffered from amnesia. Similarly, our collective or shared identities are in many ways dependent on historical knowledge, and without it we suffer.

That said, I try not to mandate which version of the past my students choose although I am clear that I see some versions as far more accurate than others (i.e. “Holocaust Denial is not good!”). I suspect that many folks who take a history course but do not major or concentrate in history, do not retain a large store of so-called historical facts. What is far more important is that they develop a critical approach to those facts, which have no meaning in themselves. From my courses, I hope that students learn how to make sense of them, use them for what they might teach about the human condition, and figure out how they might relate such knowledge to their own lives and current situations. And this is why what my courses stress, in the first instance, is historical method, i.e. those approaches to knowledge central to historical scholarship, and which share with other academic disciplines a healthy skepticism toward received knowledge.

In specific terms, this means learning how to evaluate historical evidence, the raw data from the past; learning how to evaluate what other historians have made of it, i.e. what is termed historiography or “the history of history”; and learning how to create a new synthesis, bringing one’s own perspective to bear, in light of a critical evaluation of sources and previous historians. In other words, my courses teach students how to be scholars, critical creators of knowledge, not memorizers of it. That indeed is one of the first things I say on the first day of my courses: history is NOT about memorizing names and dates!

JOAN: What are you most proud of?

Nance and spouse, Sandie Smith

NANCE: Certainly, two of my proudest moments were receiving first the Glover and, a few years later, the Drumm awards. We faculty are all proud of the high standards that we set for our students, and in return I think we recognize that they set high standards for us. Our students are tough, feisty, creative, and never satisfied with the cliché or the easy answer whether it comes from their texts, from their peers, or from their teachers. I was humbled that our seniors who are our most experienced, and I would say our most demanding Simon’s Rock students, thought me worthy of these two honors, because to me it meant that they thought I had lived up to their expectations. When we first instituted these awards, I was a bit uncomfortable, and I want to end on that note: I think all of my colleagues deserve them, because they work so hard and are so smart and dedicated. That said, I am doubly honored to have been singled out.

I admire our students while they are here, and have been in communication with a number of alums over these 30-plus years. It is very rewarding to see them make their way in the world, in ways that are smart, creative, compassionate, and ever independent-minded. I care about them all, but one thing I have to highlight as a “most proud” aspect of these relationships, is that I am still in touch with two students from my first two years at Simon’s Rock: Carlton Rounds and J.T. Way. They are both highly accomplished and highly caring individuals who have devoted themselves to the life of the mind and to service to others. Among other things, J.T. lived in Guatemala for a decade, founded a school for Mayan children, has his own foundation, is an award-winning scholar, and now teaches Latin American History at Georgia State University. Carlton who has taught in the United States and abroad, has focused on promoting volunteerism in the gay community but also well beyond it. He founded Volunteer Positive, which empowers HIV survivors through international volunteer service and cultural exchange, and is now also a director of Cross Cultural Solutions, an NGO devoted to global social transformation in the United States and outside of it. I would be honored to know these fine men even had they not been my students and, of course, I take no credit whatsoever for their myriad successes!

Finally, I am very proud of editing our book, Educating Outside the Lines. That was my project as Faculty Fellow, and it was both fun and challenging to use it to think in a sustained fashion about what we have to offer higher education not only as the pioneer Early College but also simply as an innovative college with high standards that synthesized educational progressivism with the classical tradition. Importantly, the collection was truly a collaborative work, in its development and in its denouement. We had an open process, anyone who was interested could participate; we free-wrote and gave each other feedback; and we ended with 29 authors, which included 16 faculty, two administrators, nine then-current students and two alums.

I am, of course, not a disinterested observer, but I will say that in my view, the quality of what we produced is very high. We cover aspects of the Simon’s Rock curriculum and community that range from an analysis of what our Writing and Thinking Workshop accomplishes to a consideration of the imbrication of our teaching and that of higher education in more general terms with global capitalism. And we clearly articulate what is central to our pedagogy, what I call the “pedagogical relationship.” We do not simply feature a “student-centered” pedagogy, as the current educational cliché goes. Rather, what we establish is a pedagogical two-way street. There is great respect and affection between faculty and students, and in my view it is this connection that makes what we do possible. Faculty challenge students to develop their potential to the fullest, and do their best to help them reach it. Students, in turn, make us better. As I said above, students have high expectations of us. They do not allow us to retreat into a position where we are the sole purveyors of knowledge, the sole authority. Rather we have to be ready to explain why we think as we do; to engage in genuine dialogues; and to learn from them as we respond with thoughtfulness and respect to their ideas.