- Home

- Early College

- Understanding Early College

- Our History

- "In Me is No Delay"

"In Me is No Delay"

by Ian Bickford

In July 1837, Charles Darwin sketched in his notebook the first instance of a branching structure that would govern his idea of speciation and origin. This first iteration of a now manifestly familiar image is both rough and complete, speculative and decisive, surrounded by marginal notes and leading either from or to (an important and elusive distinction) a single phrase at the top of the page: “I think.”

The sketch and the phrase together either rehearse or reverse the Descartesian axiom, convening a diagram of existence as if in completion of the grammatical phrase “I think, therefore…,” or working backward and upward through that phrase, “I am, therefore….” Thinking is either the origin or the outcome of being.

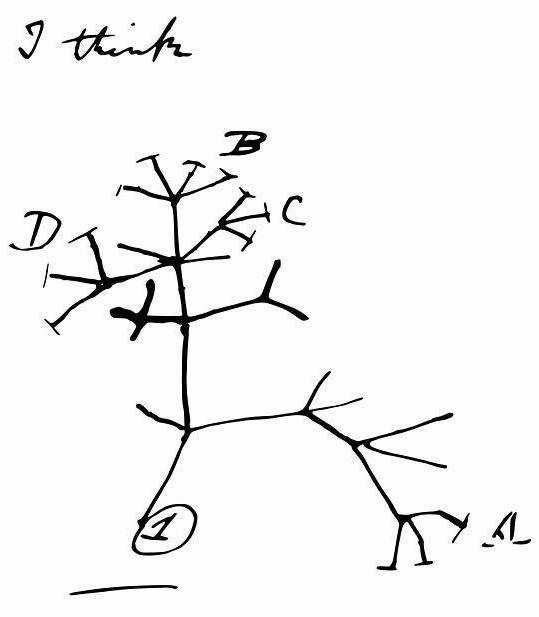

Darwin’s sketch of the first genealogical chart and the Simon’s Rock logo

The notorious pun in the title of Darwin’s much later work on human origin — which no small number of Simon’s Rockers have encountered in seminar classrooms; for me it was with Gabriel Asfar as guide — was capsuled in his argument’s germ. In The Descent of Man, to descend is both to rise, climbing the limbs of what Darwin called the Tree of Life, and to fall, alluding to the Tree of Knowledge, doubly echoing the language of the scriptural narrative that the text seeks to overturn and replace. Both narratives, Creationist and Darwinian, hinge upon the same metaphor of knowledge as vertiginous and forbidden, and Darwin’s own sense of the epistemological perils of his thinking is legible throughout his journals and in the record of his hesitation to publish his findings. He knew he was in dangerous territory, and it was with awareness that he watched the image of embargoed knowledge — the tree — emerging under his hand as he plotted the points of the first genealogical chart.

Darwin was primed to appreciate and appropriate this pivoting metaphor. As a naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle, rounding Tierra del Fuego, arriving at the Galápagos Islands, continuing west to Australia, the Cape of Good Hope, and back again to South America, it was his habit going ashore always to choose from his small shipboard library a copy of Milton’s Paradise Lost. His recursive reading of that poem informed his increasing understanding of the swarming variety of the natural world and his initial conjecture about natural selection as the framework for evolution. Milton’s resonance in Darwin’s process was more than contrast or counterpoint, more than Genesis posed against Nature in any form of stark relief. Instead, as literary critic Gillian Beer was first to note, it was in Milton’s involved syntax and descriptive abundance that Darwin found language, and, in language, license for radical rethinking of Creation:

“Darwin was to rejoice in the overturning of the anthropocentric view of the universe which Milton emphasizes, yet [Milton’s] language made manifest to Darwin, in its concurrence with his own sense of profusion, density, and articulation of the particular, how much could survive, how much could be held in common and in continuity from the past. Milton gave Darwin profound imaginative pleasure — which to Darwin was the means to understanding.”

Gabriel’s Sophomore Seminar, as the course was then called, met in classroom 11, the

furthest corner of the classroom buildings, the windows looking out on the woods and

pond beyond the Lecture Center. In those woods, as a project for Bob Schmidt’s Introduction

to Biology, I had a 10 x 10 ft. site staked out with twine, spanning the stream, and

every week I would record the life that grows there, “and swims…, or creeps, or flies,”

in Milton’s line. I remember stretching my hand in the air when Gabriel asked in full

earnest who among us would pay five dollars to kiss Nietzsche’s beard, and I remember

his experiments in futility, rolling pennies around the table, attempting to impel

them to an upright stop. In the same classroom I studied Spanish with Edgar Chamorro,

who one day, for idle reasons, approximated the Simon’s Rock sapling in chalk on the

board. The little drawing stayed for weeks in the upper left corner, and I remember

staring at it, and alternately into the woods, then down at the page as I listened

intently to Gabriel’s resonant voice reading aloud from The Descent of Man.

Gabriel’s Sophomore Seminar, as the course was then called, met in classroom 11, the

furthest corner of the classroom buildings, the windows looking out on the woods and

pond beyond the Lecture Center. In those woods, as a project for Bob Schmidt’s Introduction

to Biology, I had a 10 x 10 ft. site staked out with twine, spanning the stream, and

every week I would record the life that grows there, “and swims…, or creeps, or flies,”

in Milton’s line. I remember stretching my hand in the air when Gabriel asked in full

earnest who among us would pay five dollars to kiss Nietzsche’s beard, and I remember

his experiments in futility, rolling pennies around the table, attempting to impel

them to an upright stop. In the same classroom I studied Spanish with Edgar Chamorro,

who one day, for idle reasons, approximated the Simon’s Rock sapling in chalk on the

board. The little drawing stayed for weeks in the upper left corner, and I remember

staring at it, and alternately into the woods, then down at the page as I listened

intently to Gabriel’s resonant voice reading aloud from The Descent of Man.

“Both images speak equally to a past and to a future, both evoke invention and creativity, and both are provocations to thinking. 'I think' is both pinnacle and starting point.”

If I saw the resemblance then, I didn’t write it down, but Darwin’s first sketch reminds me now of nothing so much as the sapling that symbolizes the origin and the evolution of Simon’s Rock. The resemblance is more than a coincidence of lines. It extends into a shared attitude of discovery, ideas emerging from a process of reading and writing, the significance of beginnings as well as aspirations. Both images speak equally to a past and to a future, both evoke invention and creativity, and both are provocations to thinking. “I think” is both pinnacle and starting point.

In his most explicit allusion to Paradise Lost, elsewhere in his journals, Darwin is preoccupied with Milton’s description of Chaos as a shifting, unstable, contingent environment. Yet his later works establish broader metaphorical and rhetorical structures that speak to his iterative return to the poem, reaching its conclusion, starting again from the beginning. I imagine him reading the final lines, as Adam and Eve depart Paradise, with recognition of what is gained and lost in knowledge:

“The world was all before them, where to choose. Their place of rest, and Providence their guide: They hand in hand with wandering steps and slow, Through Eden took their solitary way.”

The poem is blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter), but indulges a few rhymes, the last in Eve’s voice immediately before the departure from the garden: to Adam, “Whence thou returnst, and whither wentst, I know”; “In me is no delay; with thee to go….” Knowing and going are wrapped in a formal as well as a thematic relationship, and while Milton’s last two lines are not explicitly a couplet—that is, they are not joined in rhyme—they are suspended in the whisper of a rhyme as the slow steps of exile reconvene the poetics of Eve’s chosen verbs, to know, to go, before emptying in the poem’s last word into a rhyme that never happens, an inarticulate and impossible wish. The last word is way. And unvoiced yet audible: to go, to stay, the essential narrative crux of the poem enclosed in syllables that are only traces within the poetic structure, hints, suggestions, ghosts.

Bard High School early College Instructors attend a workshop at Simon's Rock

As Simon’s Rock approaches the 50th anniversary of its founding and the 40th anniversary of its first conferred bachelor of arts degrees; as we mark the 15th anniversary of the Bard High School Early Colleges; and as alumni and friends gather on campus for a series of celebrations of the place and the idea that brought us all together, the College is even more what it has always been, a place where knowledge is not forbidden or restricted, where all voices announce, with Eve, “In me is no delay,” and where the tree is an invitation, not a prohibition. Like Darwin’s sketch, the sapling turns over the scriptural metaphor, returning the metaphor to new resonance and value. And like Darwin’s sketch, the sapling represents the beginning of an idea that is now firmly rooted and fully foliaged.

When Pat Sharpe and Ba Win moved to New York City in June 2001 to discover whether the Simon’s Rock idea could grow beyond the Simon’s Rock campus, there were only a handful of early entry and dual enrollment programs available nationally to younger scholars ready for more than their high schools could provide. Now there are more than 300 programs where, despite rapid speciation among them, our idea is recognizably the progenitor. The Bard Early Colleges in New York, Newark, Cleveland, Baltimore, and New Orleans are among the most celebrated and demonstrably successful public educational sites in the United States, where college faculty practice a transformative pedagogy across high school and college classrooms. The phrase “early college” is codified in federal policy in answer to the successes of our programs and of programs like ours. And the spread of the Simon’s Rock idea has produced a new paradigm in which students and families are asking not only where to go to college, but when to go to college, a question with profound implications for entrenched and layered problems of college cost, access, and completion.

Just as meaningful as the reach of our convening idea is the reach of our own community. Our 50th entering class, the class of ’16, will join a multigenerational community of alumni who remember the excitement and with it the anxiety, the hope and the newness, the affirmation and the wonder of their first day at Simon’s Rock, and the sense, on their last day, of a “world…all before them”—a complicated feeling, rich with the tensions and apparent contradictions of Milton’s lines. We go “hand in hand” yet “solitary,” and, in going, we are also staying, because Simon’s Rock is both a place and a way, a location and a direction, and if the place is a harbor for the mind, the mind — again with reference to Milton — is also a place.

It is an afterthought, but perhaps of interest, to note that Darwin started medical school at Edinburgh at 16, and that Milton entered Cambridge at the same age—embarrassed because his best friend started two years younger, at 14. Martin Luther King Jr. entered Morehouse College with early admission at the age of 15: already feeling the urgency of his future work, as his friend and close colleague Dr. Bernard Lafayette Jr. narrated to a packed house at the Daniel Arts Center at Simon’s Rock this February, he saw no reason to wait. And in Benjamin Franklin’s design for higher education, eventually to become the University of Pennsylvania, students between ages 13 and 16 matriculated from what was simply called the Academy into what was simply called the College.

We might then think of the “early” in “early college” as carrying a double meaning. Our students start college earlier than conventional expectations, but those expectations are, in fact, historically unconventional, even anomalous. College at 18, with the high school diploma as a gatekeeping credential, is a 20th-century convention, and its ossification as the only “normal” entry point is an effect of other trends — standardization, professionalization, and monetization — that Simon’s Rock and our partners in the Bard Early Colleges also challenge and seek to reverse. Our early model is both new and old, late and early, experimental and proven, exploratory and situated.

To go. To stay.

Ian Bickford is a former provost and vice president of Bard College at Simon’s Rock. This essay originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of the Simon’s Rock Magazine.